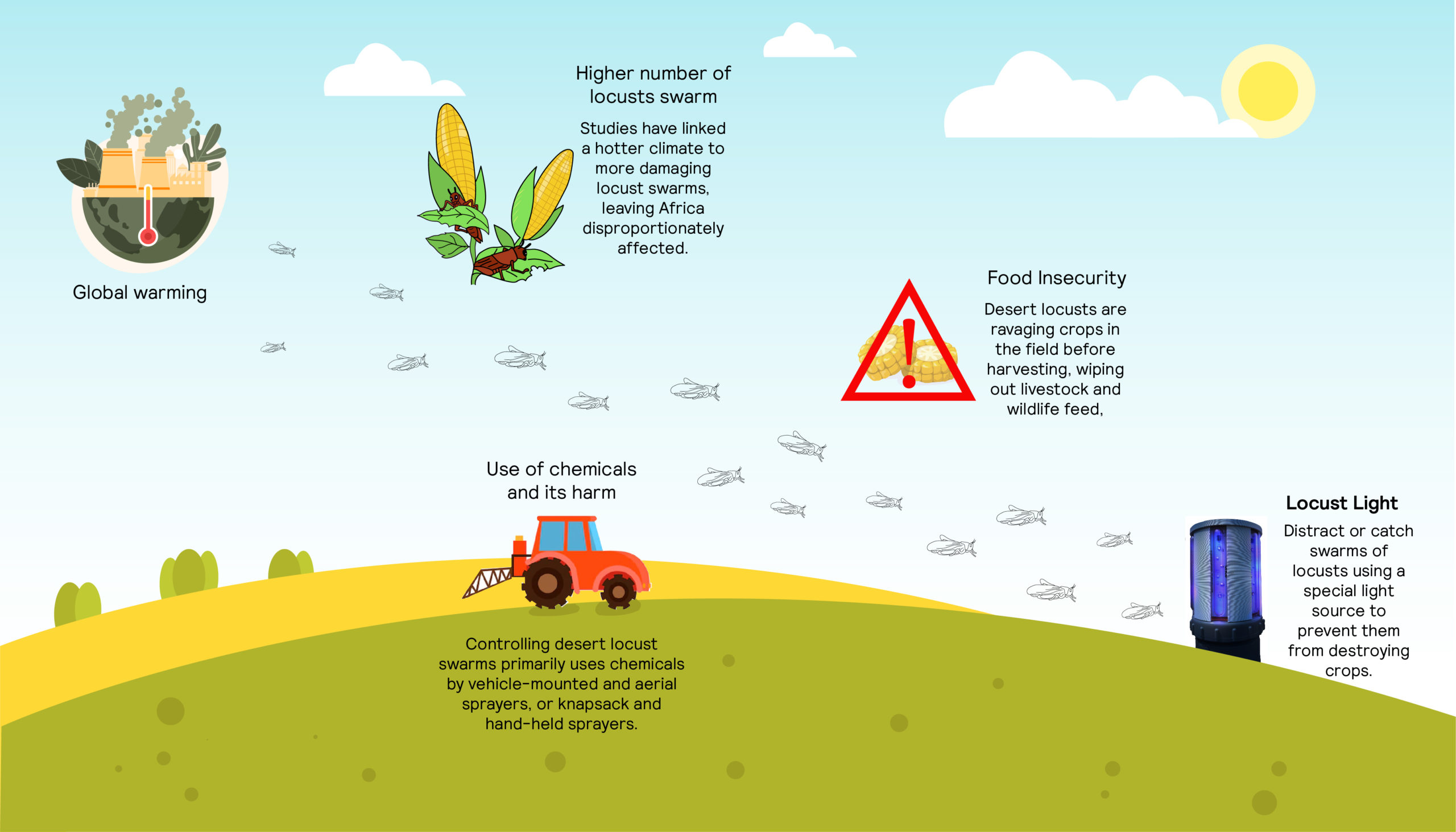

Locusts, scientific name Acrididae, are a global insect related to grasshoppers. When discussing locusts, one would often see the words: plague, pests, damage, destruction, swarms, devastation. They cause immense damage to agricultural crops in areas where this damage is felt most acutely. The Desert Locust, the species that delivers the hardest economic impact, is a threat to 20% of the Earth’s land area and 10% of its population. Over 60 countries are vulnerable to swarms. Swarms can reach over 400 square miles in size with up to 100 million locusts per square mile. As each can consume their weight in plants every day, they can cause damage on a devastating scale.

Locusts are also a fabulous source of protein, containing between 13-28g/100g for adult locusts. To put that into perspective, beef has 19-26g of protein per 100g. However, the increased use of pesticides to control swarms can introduce deadly toxins into their systems, making harvesting these edible pests a challenge. Someone should be working on a safe way to capture and harvest these pests, thus minimizing the destruction of crops while generating protein-rich food in some of the areas in the world hit hardest by starvation.

Well, someone is working on exactly that, and that person is Jaap Schuuring, Signify Head of Customer Education. I interviewed Jaap to find out more about his project to turn pests into protein.

Well, someone is working on exactly that, and that person is Jaap Schuuring, Signify Head of Customer Education. I interviewed Jaap to find out more about his project to turn pests into protein.

Hello Jaap, I’ve known and worked with you for over 10 years now, and you have always been passionate, driven, and especially innovative. This is such a win, win, win idea and project. I first want to congratulate you on it. I think it is an amazing concept.

Thank you, Tom. It has been always a pleasure working with you. It also triggered many ideas in the educational domain we both are active in.

I would not call this a project as such; it is more of an extremely exciting journey we are on. At its heart is an artificial light source that acts as a trap to catch or distract locusts.

And, as with all journeys, it is not predictable when and where the journey ends. But we are slowly getting there and hopefully will see the positive result we have in mind: controlling locust swarms and supporting farmers and communities with an issue that can impact food security.

We are currently in a pilot phase, testing and collecting results from a trial to catch locusts in an artificial light trap. We will use the results of this trial to design the next steps.

What was the genesis for the idea for this journey?

It all started when I was watching a news item about locust swarms appearing in Africa.

I wondered how those species would react to light and how light could be used to “control” such swarms in Africa and in other places.

Just as humans react to lighting in many ways, so do animals, and in this case insects, all with their own responses and behavior.

I do not have a research background but just a huge interest in exploring, figuring out and learning more about certain topics that have a strong link with environmental and health and well-being. Being a creative thinker and actionable entrepreneur helped me start to think about a concept that resulted in a first prototyped potential solution.

When did this journey start?

It started a bit more than two years ago. That might seem like a long time ago but as we all know, it coincided with a global pandemic situation. This impacted the way we develop, co-create, and test the solution.

Starting such a process begins with exploring. It took a long time to figure out how these types of insects respond to light. Then, it was a matter of connecting the dots and developing an engineering sample that can be used for testing purposes.

I’m sure you did not work on this alone in a room. Who are some of the key people involved, and what is their involvement?

I was lucky to have my colleague Maurice Donners, a Signify scientist with great knowledge on the topic, joining me in the early stages and Harry Verhaar (Head of Public & Government Affairs) supporting and connecting us with the right people internally as well as externally. Our team built engineering samples, and my colleagues in Africa connected us with the right institutes to perform tests on the ground. They also helped to give us direction, keep focus, and stay close to the problem statement.

The Signify Foundation supported this from the moment they got involved, just after we finished the first prototype. The Foundation’s mission is to light the path to a more equitable and inclusive world. I would encourage you to look at what they are doing, as it is very inspiring.

This year, colleagues from Signify joined the journey by nominating projects across the world where lighting plays a key role in enabling the invisible to become visible. The locust light was part of this.

What point is this project at in 2022?

We are about to receive results from the scenario testing from our team in Kenya and South Africa. This is going to be crucial for the next phase of our journey. Depending on the outcome of the tests, we hope to drive it further with the support of the Signify Foundation.

What has been the global feedback?

There is interest from different angles, like the United Nations and national authorities. Agricultural ministries are interested in preventing pesticide spraying. Insects that are sprayed but not killed also spread the chemicals and make it harder to use insect protein as a food source.

There is also interest from the scientific domain. They are already involved in the testing phase.

But it is too early to tell – we need to wait on the test results before we can say anything definitive.

Where are you testing/planning to test?

We will be testing this light in the outdoor space on locations in Kenya and South Africa together with universities and students.

What exactly will be tested is decided in close cooperation with the teams and Universities and our research colleagues. Data will then be collected and processed. This will show us how locusts respond to the light when exposed to it.

As you can imagine, there are different scenarios we are looking at. One of the partners will be the University of the Free State (Bloemfontein, SA) – where we may also perform tests on other species.

There is much more to be explored. With the right involvement, we can learn quickly.

What types of food can be made from this system solution?

First you need to catch the locusts. Once caught, they can be converted into raw materials for food production. Locusts are protein-rich insects. This is part of the whole concept.

We do not yet know how this is best achieved – for example, creating powders or pastes, and what training will be needed to make this a reality. This needs to be explored further together with partners with more experience in food production and processing. We do prefer a local approach, if possible, but this is challenging because it is not always predictable where locusts will appear. It may in fact be better to transport them to a centrally organized processing facility. These steps are yet to be fully explored in detail. But I do expect, with the support of authorities, we will be able to find a solution quickly.

Have you tried it? Does it taste good?

Yes! There are already several locust protein products on market. This is not a new thing. The way you catch them is new. And they taste pretty good. It depends how you prepare it.

You have mentioned that education is going to play a crucial role. Can you elaborate?

What I have in mind is training farmers on how to process locally caught locusts into raw materials for food production, which might have an impact on food scarcity.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of this venture, thus far?

The collaboration with my colleagues, co-creating a potential solution for a huge problem. This was and still is an exciting learning journey and I certainly hope we are able to present positive outcomes soon.

What facet has been the most frustrating or challenging?

The delay caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has caused disruption in testing the potential solution. Locusts do not always appear each year in the same places. Moving around was crucial, and that was not always allowed because of national and local lockdowns.

What will success look like, to you, going forward?

Success (to me) means that we are able to contribute to addressing a huge problem, supporting local communities by controlling infestation of these insects. We aim to keep those insects away from crop fields and grasslands to prevent them eating everything, resulting in food scarcity for humans and livestock.

Jaap, any closing remarks for the readers?

“I think we need to change the “catching two birds” idiom into a new one – “catching two locusts with one stone”. Here we have a potential lighting solution that preserves farmers’ food and income, while at the same time providing a rich source of protein for humans and livestock.”

This is a fascinating project and journey, the ramifications of which could be huge. As an industry, we should be very proud at how we have been able to cut back on energy consumption over the past 15 years. We are well on our way with understanding how light and darkness affect our health. Could light assist with food scarcity and pest control? It is a hopeful thought. And if I know Jaap, it will get done.

I’ll have two locust burgers with sriracha, and a mint protein shake to go, please.